- Details

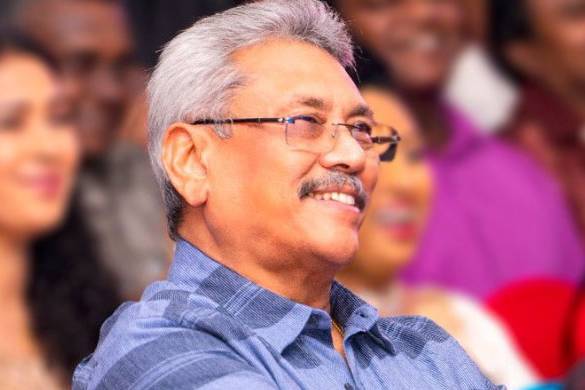

SLPP Presidential candidate Gotabhaya Rajapakse officially launched his election manifesto at a colorful event held at the Nelum Pouna, Mahinda Rajapakse theatre last Friday in the presence of the religious clergy, political allies, the diplomatic corps, professionals and other party loyalists. Soon thereafter, I observed various references made to the manifesto by various individuals / groups in both media and social media platforms. One such reference that captured my fancy was a comment made to the effect that ‘the manifesto only confirms your worst fears. Not a single word on human rights’. The fallacies of this observation become evident when looking at both the process of the manifesto formulation and its content.

- Details

With the election of Gotabaya Rajapaksa as the President in November 2019, there seems to be much interest and talk on integrating merit and technocracy into the country’s political life and governance system. These discourses are manifested in the slogans of various lobby groups seeking to promote the election of newer, more educated and professionally qualified representatives to Parliament as well as in the various initiatives taken by the President to ensure that qualified and competent persons are appointed to top positions in state run institutions.

- Details

With only a few weeks left for the 2019 Presidential Election, two questions seem to dominate our social conversations and news coverage: “who will win?” and “what will be Sri Lanka’s political destiny?” In the absence of country-wide scientific polling, the first question is typically answered by using anecdotes, quasi-scientific, social media or social network specific speculations or gossip. The second question, which categorically stems from the liberal quarters of society, is a long-winded lament about the “cruel dilemma” of having to choose between a “neo-conservative” coalition and weak political formations putting up a brave fight to hold on to the last straw of the country’s democracy. The first question can be useful and interesting, as it gives an opportunity to unleash one’s hidden statistical animal and pretend to be a polling-data expert for a few more weeks. The second question and the story of doom and fear it follows, is rather pedestrian. It ends rather abruptly, by contending that in 2019, the ‘democratic voter base’ is divided against the allegedly large “un-democratic” segment of the population supporting the ‘counter-democratic, authoritarian dark knight’ – Gotabhaya Rajapaksa. The Liberals have come up with a simple, black-and-white picture in which Sajith Premadasa is exalted as great Liberal, and Gotabhaya Rajapaksa as a scary neo-conservative. Not only am I sceptical about the theory that Sri Lankan society is polarised over democratic values, but I also feel that the Liberals, in a moment of dejection, are not asking relevant questions that would help advance a political reading of the growing demand for “new authoritarianism” in Sri Lanka.

- Details

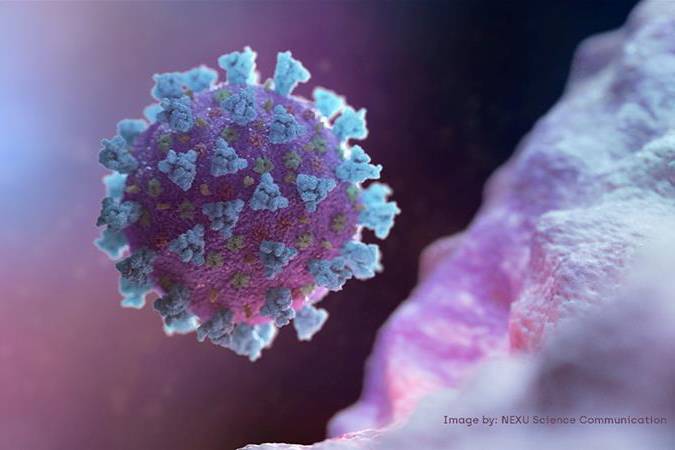

කොවිඩ්-19 යනු ප්රධාන වශයෙන් ගෝලීය මහජන සෞඛ්ය අර්බුදයකි. නමුත් එම අර්බුදයට ප්රතිචාර දැක්වීමේදී අපගේ රටේ ආර්ථිකය, සමාජය සහ දේශපාලනය අප සංවිධානය කරගන්නා ආකාරය පිළිබඳ ගැඹුරු ඇගැයීමක් කළ යුතු වේ.

- Details

ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදය ගැඹුරු කිරීම සඳහා විවිධ ආණ්ඩු, විවිධ පරිශ්රම දරා ඇති බව ඉතිහාසය පුරා අපි දැක ඇත්තෙමු. ශ්රී ලංකාවට නිදහස ලැබීමෙන් පසු ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථා සංශෝධන සහ නීති ප්රතිසංස්කරණ මගින් මේ සම්බන්ධ නොයක් මැදිහත්වීම් විවිධ කාලවකවානුවල සිදු කර ඇත. එසේම, මේ පිළිබඳ පවත්වන ලද සාකච්ඡා සම්මන්ත්රණවල ද නිමක් නැත. බොහෝ විට ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ප්රතිසංස්කරණ සඳහා වන මෙම මැදිහත්වීම් ජාත්යන්තර න්යාය පත්රයන් සහ, එකී සංකල්පයන් මත පදනම් වූ, නීති ප්රතිසංස්කරණ සහ ආයතනික ප්රතිසංස්කරණවලට සීමා වූ බව විශේෂයෙන් සඳහන් කළයුතු නොවේ. බොහොමයක් ප්රතිසංස්කරණ මගින් පුද්ගල නිදහස ශක්තිමත් කිරීම දේශපාලන සහ සිවිල් අයිතීන් ශක්තිමත් කිරීම සහ රජය තුළ විවිධ ජාතීන්ගේ පදනම ව්යාප්ත කිරීම සඳහා අවධානය යොමු විය.

- Details

In less than 12 months, our island nation had to confront two devastating phenomena – both of which came through cross-border transmission, invisible to the eye in any material form, yet causing devastation in incredible dimensions.

- Details

”මිනිස් ඉතිහාසයේ ලොව ව්යසනකාරීත්වයන් පසුකොට පැමිණ ඇති අතරම, කොරෝනා ව්යසනය නව ලෝකය තුළ යම් රටක් අත්පත් කරගත් සියලු සක්යතාවයන් සුනු විසිනු කොට දමා අවසන්ය. දැනුදු පවතින ව්යසනයේ අනාගත ලෝකය හා එහි රාජ්යයන්ට අත්පත්වන ඉරණම හා ලෝක බලවතුන් ව්යසනය හමුවේ දණ ගසා සිටීමෙන් පෙන්නුම් කරනුයේ කුමක්ද ? කොරෝනාවෙන් පසු එළඹෙන ලෝකය කවරාකාර ද ? මේ ඒ සම්බන්ධයෙන් කොළඹ විශ්ව විද්යාලයේ දේශපාලන අංශයේ කථිකාචාර්ය සුමිත් චාමින්ද සමඟ Lankatarget.com කළ කතා බහයි..,”

- Details

- Details

නිදහස ලැබීමෙන් පසු ශ්රී ලංකාව සුභසාධන ප්රතිපත්ති රැසක් හරහා රටේ මානව සංවර්ධනය ඉහළම තැනකට ගෙන ආ රටකි. අධ්යාපනය හා සෞඛ්යය පිළිබඳ නිර්ණායකයන් අනුව දකුණු ආසියාවේ ඉහළම තැනක සිටින අප, වෙනත් ඉහළ සංවර්ධනයක් ඇති රටවලට සාපේක්ෂව ද වඩා හොඳ ස්ථානයක සිටී.

- Details

On 25 September 2015, at the 70th session of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in New York, 193 countries adopted a new development agenda, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The new development framework is expected to inform the development planning processes of member states until 2030 and serve as a benchmark for assessing development outcomes of member states in the post-Millennium Development Goals (MDG) phase.

- Details

‘යහපාලන’ ආණ්ඩුව බලයට පත්වී වසර හතර හමාරක් ගතව ඇති මේ මොහොතේ ආණ්ඩුවේ කාර්ය සාධනය ගැන අපට ඇත්තේ බලවත් කලකිරීමකි. ආණ්ඩුව පිළිබ`ද ජනතා විශ්වාසය පළුදුවීමට තුඩුදුන් ඕනෑතරම් හේතු මේ වනවිට නිර්මාණය වී තිබේ. මින් ප්රධානතම හේතුව වන්නේ බලයට පත් ආණ්ඩුව ඉදිරිපත් කරන දේශපාලන ප්රකාශ සහ ඒවා ක්රියාත්මක කිරීමේ දී ඇති වී තිබෙන දරුණු පරස්පරතාවයි.

- Details

‘දූෂණය‘ යන්න ඉතා පුළුල් ලෙස නිර්වචනය වී ඇති වදනකි. එනම්, දූෂණය යනු ජනතා බලය තම පෞද්ගලික ලාභ ප්රයෝජන හෝ තම පවුලේ, මිතුරන්ගේ, වර්ගයේ, ජාතියේ හෝ දේශපාලන පක්ෂයේ ලාභ ප්රයෝජන සඳහා භාවිත කිරීම යි. දූෂණ පිළිබඳව එල්ල වූ චෝදනා ලොව බොහෝ රටවල ආර්ථික ක්රමයේ වර්ගය සහ ප්රමාණය නොසලකා හරිමින් විවිධ ආණ්ඩු බිඳ වැටීමට ද, ජනාධිපතිවරුන්, අගමැතිවරුන් ඇතුළු ප්රබල දේශපාලකයන්ගේ පාලන බලය අවසන් කිරීමට ද හේතු වී තිබේ.

Page 3 of 4